Elechi Amadi was never introduced to me. The benefit of a proper introduction, which largely was a recommendation of text, by the school curriculum didn’t come my way with him. But somehow, the African Writers Series (AWS) had conscripted my lunch break and other ‘obscene’ hours (apologies to my late father whose love for Mathematics is to blame for the obscene nature of literature) dedicated to the mystical world of literature that took me to many lands.

Somehow that afternoon marked my completion of the Simplified Series of the English classics and an astounded librarian started incredulously at me as if searching for evidence to show where my petite frame, hid all the words I must have swallowed of the Series. A defiant smile played upon my dark, round face as I lapped up pride in my ability to keep this librarian busy.

There had always been a war going on – him and I. I gave him his first assignment most mornings and made sure his lunch break was short-lived by my prompt attendance to get him busy. He retaliated by suggesting books, out of my systemic turn, to keep me away from him. But when that didn’t seem to work, a return of his recommendations usually became an opportunity to do a test that never did my classwork any good. So he stared; and I glared.

The challenge was sure to brew but for how long to ensure speedy drunkenness was the real McCoy. Life sprang to his eyes and age cheated on me with the speed of his thinking. ‘Have you read any of the African Writers Series?’

‘No’.

The word escaped in a blurt and I felt trapped and drained. He was up to something. Pointing to a well arranged, clean row of some orange-coloured texts; he added, with a smile that Tom would have given Jerry from a successful putt into a hole, ‘should I pick one for you?’ ‘What a birdie!’ everything about him was saying except his smiling eyes and the suppressed excitement his voice betrayed.

From the row, none seemed to have lost any weight. Each one stood well fed with words encapsulated in pages standing in a guard procession for inspection.

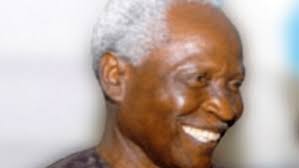

‘No, thank you.’ I almost screamed. I was caught. I wanted out. In a blinding surge, I made a dash for the row and took out one I didn’t look at till I raced to the notebook that was the lending register and did his job for him. Once out of his presence and into the afternoon sun, I stopped to calm my racing pulse and glanced at the book in my hand. The author-shot got Elechi Amadi giving me a stare as if saying ‘so what?’. I quickly turned to the front cover to be greeted by The Concubine. I looked at Elechi again and said ‘hello.’ And we became friends.

He took me to the rustic setting of the far east of the Nigerian country and I explored the bliss of village life and the simplicity of expectations, and the community. I had just concluded a joy ride with Emily Bronte through Wuthering Heights and the tourist euphoria was yet to depart my spirit. Even though I lived in the village invisibly with them as I spied, courtesy of my friend, Elechi, I was almost ecstatic at the ghost-calling privilege of a civilisation I almost never knew but was part of.

I began to understand the definition of love more than the Sunday service would teach. Christ dying for us began to make some sense and the supra-sensible factor became a thread weaving patterns of its own in some discordant order. Why the supra-sensible was to be appeased because of a clash of interest was quite confusing. I never really could fathom how and why some spiritual abstract could commit itself to a corporeal necessity in the act of love. Why, Christ became man to love man? How shy could this spirituality be that like a full grown adult would dip its hand into a child’s bowl of morsel meal for some shared pleasure of assuaging hunger?

The world took on a new meaning to me. It was not merely man’s world and man, indeed, was not a domination of it. The value of order that was enshrined in a relationship of dependency where one party was the victim of another’s whim petrified me. Yet Elechi took me through the experiences of shared passions like hope, joy, and commonwealth, with which one could get drunk and forget the rascally partnership of some spiritual reality.

Nature was the balm of existence. Itself demanding nothing but a simplistic patronage not some technological calibration fraught with danger. Though far in time and place, I could find the possibility of paradise and the rhythm of Eden in the earthy surround. Paradise must have been in Africa.

I wanted to ask Elechi why there had to be so much dependence on these gods who played childish pranks on man’s high stakes. I wanted him to tell what he found so intriguing in the details of community habitat. I needed him to show me other paths to reduce the drift to the new world’s bizarre nature and how to dwell in the comfort of our culture, my culture. There was quite a lot we have to discuss.

But he was surfing several waves. Whether that was what he wanted or what he had to do I would get him to say. He felt the pain of the wounded, he knew the sting of the pellet stoned on people. He traded on the earth for his people. He professed severally from his well of wisdom. Then, in the smallness of wee hours, he spoke words into white pages; of things, people and places, their identities, travails, and (lost) causes.

It was deep the great ponds fettered us, the slave, and made us the concubine to our own mysteries. But he only waited for the sunset in Biafra to prove the futility of Isiburu before his candidature to the land where the sun never sets, and I couldn’t ask him anything,