“Most reporting on the conflict is using questionable framings, suggesting it is purely driven by a desire to plunder the region’s rich mineral resources.”

By Judith Verweijen – The capture of North Kivu’s provincial capital, Goma, by the M23 armed group last month has multiplied international coverage of the forgotten crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Yet most reporting on the conflict is using mistaken framings, suggesting it is purely driven by a desire to plunder the region’s rich mineral resources.

The conflict minerals narrative contains several tropes: Proponents claim that the M23 and its Rwandan allies launched the insurgency to loot large quantities of minerals from neighbouring DRC; that Western electronics or tech corporations buy violently exploited minerals and thus become complicit in the conflict; and that the war is driven by competition for so-called critical mineralsrequired by the energy transition.

There is nothing new or surprising about blaming the M23 crisis on greed for resources. Conflict minerals have been the primary lens through which international media have approached conflicts in eastern DRC for almost three decades.

This story has an intuitive appeal: It offers a clear narrative with a primary and very tangible culprit (Western multinationals), a direct link to the public (who own a laptop or mobile phone), and a neat solution: Stop buying ‘conflict minerals’ and sanction wrongdoers.

Whereas war in other settings is often acknowledged to be the product of a more complex type of geopolitics, history, and ideology, warfare in Africa is reduced to naked greed.

But as much as it is seductive, the narrative is incomplete and false. And, as we have seen throughout the past decade, it can be highly dangerous, leading to poor policies and failed peace efforts that ultimately hurt the very people affected by violence.

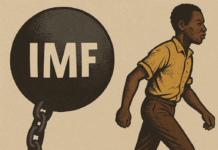

Ultimately, the conflict minerals narrative is grounded in a colonial worldview, where Western producers and consumers are the ultimate arbiters of suffering in eastern DRC. It is therefore deeply inscribed in White Saviourism. It does not acknowledge African agency, let alone account for a changing world where non-Western corporations have become major electronics producers.

Above all, the conflict minerals narrative reproduces a problematic kind of African exceptionalism. Whereas war in other settings is often acknowledged to be the product of a more complex type of geopolitics, history, and ideology, warfare in Africa is reduced to naked greed. Abandoning these tired tropes will be indispensable for creating a viable path towards peace.

Complex conflict dynamics

Natural resources do play an important role for both eastern DRC and Rwanda’s political economy, and it is true that the return of the M23 in 2021 correlates with a sharp rise in Rwanda’s mineral exports, as per official statistics.

Moreover, the M23 does benefit from mineral exploitation and trade. Last year, for example, the rebels seized the Rubaya mine (one of the world’s biggest coltan deposits), and are now earning some $800,000 a month from taxation according to UN estimates.

However, the Rubaya takeover came more than two years after the insurgency started, and cannot therefore be considered its proximate trigger, nor do the mines constitute the group’s sole means of making money.

Other flagship mines in the region (including cassiterite in Bisie) remain out of the M23’s range, as do DRC’s enormous deposits of copper and cobalt – a key mineral for producing electric vehicle batteries – which are concentrated in the country’s southeast. This region is not affected by conflict but is part of multi-billion dollar supply chains characterised by large-scale international and domestic corruption.

What then drives the M23? On the one hand, there are the interests and ambitions of the M23’s leadership. These include individual interests linked to amnesty for past violence as well as wider political and military claims. Whereas the latter initially centred on political participation and refugee return for the Congolese Tutsi community (the community from which most M23 leaders hail) the rebels are now articulating a more national agenda, threatening to march to Kinshasa, the capital. It is unclear whether that threat is rhetoric or based on a genuine plan.

On the other hand, Rwanda, which the UN says has several thousand troops supporting the M23, has had a steady interest in exerting influence over eastern DRC for the past 30 years. Not unlike DRC’s other eastern neighbours, pursuing similar objectives, Rwanda’s motives for influence reflect a mixture of political, security, and economic reasons, often charged with identitarian narratives. These ambitions have inspired repeated interventions from several of DRC’s neighbours since the 1990s, including to fight enemies of their own that found refuge in eastern DRC.

Successive Congolese governments have helped to perpetuate this security predicament: Unable and unwilling to build an army capable of protecting territory and population, the Congolese security forces have become part of the long-standing violence in eastern DRC.

DRC also struggles to resolve deep-seated conflicts over identity, land, and authority that keep fuelling successive wars and insurgencies. Most armed groups and army factions involved in the violence, in turn, have developed a diverse range of revenue-generating activities, of which mineral exploitation and trade is but one in many options.

In sum, eastern DRC’s mineral trade happens very much in symbiosis with broader instability. And as much as they are affected by conflict and play a part in it, supply chains are more complex than misleading narratives around conflict minerals suggest.

Who benefits?

Contrary to the story that the M23 has been crucial for assuring Rwanda’s access to Congolese minerals, the country has such access regardless of whether it sponsors rebellion or intervenes with its own troops. To a large extent, this is because tariffs and taxes in Rwanda are lower, enticing Congolese producers to export to Rwanda both legally and illegally. This implies they do so willingly and not necessarily at gunpoint.

Nor is coltan, which transits from M23 areas through Rwanda into global supply chains, Rwanda’s most important export product, ranking far behind tourism and gold in terms of export value. Gold brings in over 10 times as much as coltan.

While official gold exports by Rwanda multiplied in recent years, and much of that gold originates from DRC, the link with the M23 remains unclear. To date, the group has not advanced to any of the DRC’s most important gold mining areas, whose historical commercial links span across the region, including to Kampala (Uganda) and Bujumbura (Burundi). This aligns with recent research findings that eastern DRC’s gold business tends to thrive in the absence of active conflict.

Another persistent story is that Western electronics producers are the primary beneficiaries of Congolese minerals exported through Rwanda. This story focuses on coltan, which is often cited as the paradigmatic ‘conflict mineral’, and is needed to produce capacitors used in laptops and cell phones.

Yet it remains unclear how and why armed conflict would be beneficial to the electronics producers using coltan. And it is important to note that these are not exclusively Western, as several Asian countries are also key manufacturers of electronics.

These producers benefit most from a steady and stable supply of coltan to meet demand and keep prices low. They may consider armed conflict to be non-beneficial because it creates instability in mining areas, which can lead to supply shocks and therefore raise prices.

Another reason why armed conflict is not necessarily in electronics producers’ interest is conflict minerals legislation, specifically section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act in the US and the EU Conflict Minerals Law. On paper, these laws oblige Western corporations to be transparent about their supply chains and prevent buying minerals from areas where they would finance conflict. The result has been a range of traceability initiatives that have added complex administrative layers to supply chains.

Unfortunately, a decade of experimenting with these initiatives has shown that they do little to bring peace, yet have detrimental effects on those depending on mining for their livelihoods.

One reason for this is that the operational costs of these schemes are borne by local miners and traders. Notably, this is the case with the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative (iTSCi), the first and most developed traceability programme in the region.

Strikingly, iTSCi imposes higher operational costs in DRC than in Rwanda. Rather than improving supply chain oversight, iTSCi has therefore encouraged the smuggling of Congolese minerals to Rwanda, independently of the M23 rebellion.

Recent calls, meanwhile, for banning minerals from DRC and Rwanda – which electronics producer Apple already abides by, after the Congolese government launched a complaint against its European subsidiaries – could have dire consequences for the thousands of people depending on artisanal mining for their livelihoods.

The perverse effects of conflict minerals initiatives remind us that inaccurate narratives on the conflict in eastern DRC are not only an inconvenience but can further exacerbate the very problems they pretend to tackle.