I have always found it intriguing to read a good story in prose, poetry, and play form from persons who have been distanced from there homeland. I wonder about how they feel – I mean about the food, the houses, the freedom, the cultural indulgences, the relationships, the social ethics, etc. I would give an arm and a leg to find out if they could interpret themselves to a meaning of their lives; their reality, and perhaps the psyche of their new roles.

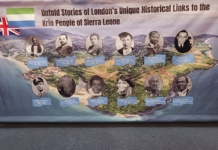

The role of Heinemenn Educational Books (HEB) in the development of African literature cannot be underscored by any means. It threw up what Africa and Africans are. It spelt an identity of cultures and proved humanity beyond colour of creed. Above all, it restored some dignity and bestowed respect.

But could that have been only as far it would go? Heinemann suffered inertia and the late Chinua Achebe resurfaced with it carrying a banner. But the hands that bore the banner soon yielded to a common fate: death. But the banner must not fall, lest those who should see it: our children and our children’s children think the grounds upon which they should stand were never conquered but offered to them as ‘gifts’.

So what becomes of the themes and settings of the poems, stories, plays which we must labour our farthings to behold? A sneaky thought slips into my mind to ask, ‘Do we see enough to know what we have or have had or may have?’ I though that was cheeky: ‘What do you mean? Get outta here!’ Another mischievous thought echoes somewhere from the back of my head: ‘But how do you celebrate what little you put on show when it does not sell itself to those who m,ust know that you are an original and not an aboriginal?

I wasn’t going to let all these thoughts run me amok after all I am me. I am the ‘one’ not them. I have a name, they don’t? My ego felt fed and won’t to blab but an ego-deflating jab hit me below the solar-plexus. ‘These are the voices of your ancestors, christianised as your ‘guardian angels’, westernised as your ‘common sense’, … . But it actually is YOU in all your DNA and wisdom of your culture and identity showing the principles, values, and social ethos which make you a brand.

I remember stories told under the tree at the centre of our cluster of huts in the village: told by the elderly filled with song and dance, laced with proverbs and adages, branding us to the soul to being humans with integrity and dignity, selfless and true, condemning malice and avarice. I remember the riddles in poetic bursts that induce rewards that gladdened the stomach and not ‘stars’ soon forgotten in the toy heap or used as ‘evidence’ for the state considerations.

But we loved those moments, we remembered the stories, we knew their morals and they were laws in the family, clan, and culture so you could win your case. ‘When a child washes his hands, he can eat with elders’ – Things Fall Apart. We were not laboured beyond our years; we were always ‘contemporary’.

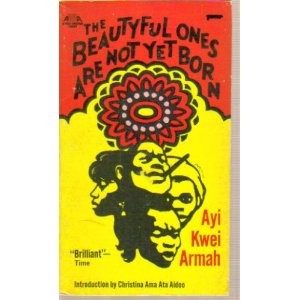

It reminds me of Rama Krishna in The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born.

“Then solemnly like a man in great distress of spirit, he would go to another book of another stranger whom he called sometimes the prophet and sometimes Gibran, and read:

‘Would that you could live on the fragrance of the earth, and like an air plant be sustained by light. But since you must kill to eat, and rob the newly born of its mother’s milk to quench your thirst, let it then be an act of worship… And the man wondered what kind of sound the cry of the chichidodo bird could be, the bird longing for its maggots but fleeing the faeces which gave them birth.”