By Henry Brefo

By Henry Brefo

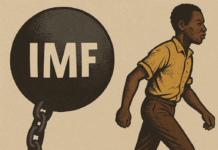

The politics of homosexuality in Africa is largely couched in the language of North vs. South hegemony. Consequently, African leaders have been increasingly adopting resilient attitudes towards the criminalising of gays as part of an exercise in national sovereignty.

The signing of the anti-gay bill by the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, casts fresh light on the politics of homosexuality in Africa and the danger of the West’s ‘pro-gay for aid’ style of intervention.

Since the announcement of the Bill, Western governments have threatened to cut aid to Uganda if it becomes law. According to the World Bank, Uganda receives up to $2billion in foreign aid from Western countries every year. Museveni’s decision to sign the bill contrasts his previous reasons for putting the bill on hold a week ago, stating in a letter to parliament that “there are better ways to ‘rescue’ gays from their ‘abnormality’ than jailing them for life.”

“The new law punishes first time offenders with 14 years in jail,” according to the BBC, and allows life imprisonment as the penalty for acts of “aggravated homosexuality”. It also makes it a crime not to report to the authorities any knowledge of gay partnerships or incidents of same sex unions. According to a government spokesman, President Yoweri Museveni wanted to affirm Uganda’s “independence in the face of Western pressure”.

Last month, Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan also caused a storm when he signed a ‘Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act’. This new law criminalizes proprietors of homosexual clubs, associations and organizations with penalties of up to 14 years in jail. The international community has repudiated the law as unacceptable. US Secretary of State John Kerry condemned the law as “a dangerous restriction on freedom”. Britain also affirmed that, “the UK opposes any form of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation,” according to Reuters”.

Nigerians in the Diaspora have also expressed their discontent towards new law. The renowned Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, commenting on her government’s actions, warned that ‘”he law is ‘unafrican’. It goes against the values of tolerance and ‘live and let live’ that are part of many African cultures”. That said, lawmakers supporting the Bill deem it to be “in line with the people’s cultural and religious inclination,” according to Reuben Abati, the president’s spokesman. However, the president, alongside other high officials in government, has remained silent. Since the passage of the law, there hasn’t been a whiff of protest or demonstration in Nigeria.

Even Ghana, widely considered a bastion of cultural tolerance and peace, found itself in the fray of the controversy regarding homosexuality. Two years ago, pressure from David Cameron to have the late President Atta Mills’ administration decriminalise homosexuality by threatening to cut aid to Ghana resulted in a national rebuff. His successor John Dramani Mahama, when asked whether he supported gay rights in Ghana – specifically gay marriage, on a visit to Georgia at the invitation of Kennesaw State University, simply averred, “It’s a difficult situation, but I guess it’s something that –– it’s very difficult to comment on because often it creates more problems.”

Under section 104 of the Ghanaian constitution, ‘unnatural carnal sex’ is deemed criminal, and legally warrants a conviction to imprisonment for a term of not less than five years and not more than twenty-five years. Consequently, homosexuality is commonly interpreted as unnatural carnal sex – an error of judgement which, according to lawyer John Ndebugri, does not satisfactorily warrant the criminalisation of homosexuals. In a press address to the president, he challenged his position on homosexuality, and contends that “it does not constitute law”. The Ghanaian journalist Justice Sarpong also questioned the meaning of ‘unnatural carnal sex’ and concluded that “there is no law in Ghana that makes homosexuality” a crime. Unnatural sex, according to the constitution, is defined as sex in an unnatural way. President Atta Mills based his decision on homosexuality, which is currently supported by his successor, as the reason that the “UK did not have the right to direct to other sovereign nations as to what they should do” since Ghanaian society’s ‘norms’ were different from those in the UK. The government position on homosexuality has enjoyed popular support in Ghana.

Senegalese President Mackie Sall has echoed similar sentiments in a statement warning other countries to refrain from imposing their views and values. “We don’t ask the Europeans to be polygamists,” Sall said. “We like polygamy in our country, but we can’t impose it in yours because the people won’t understand it. They won’t accept it.”

Notably, Gambia’s President Yahya Jammeh outdid them all in his snub at the Western pro-gay for aid agenda. Last Tuesday (February 18), Jammeh gave a speech on national TV to mark the nation’s 49th anniversary of independence from Britain , which summed up his position as follows: “ We will fight these vermins (sic) called homosexuals or gays the same way we are fighting malaria-causing mosquitoes, if not more aggressively.” He added: “we will therefore not accept any friendship, aid or any other gesture that is conditional on accepting homosexuals or LGBT as they are now baptised by the powers that promote them (…) As far as I am concerned, LGBT can only stand for leprosy, gonorrhoea, bacteria and tuberculosis; all of which are detrimental to human existence.”

Western threats to cut aid for gay rights in Africa have rendered the debate volatile. Instead of the emphasis being placed on human justice and equality, sovereign pride has taken precedent. This show of African sovereign pride has also enlisted in its arsenal of legitimacy cultural values and religion. The often-cited religions from which moral support against homosexuality is commonly sought are not even traditionally African. Western involvement in such domestic issues is bound to be unhealthy and dangerous for the group whose rights they claim to be fighting for.

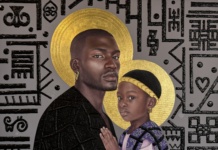

Clearly, if any traction is to be gained at all regarding the issue of legislation over homosexuality in Africa, it would have to stem from the grassroots. Discourses on homosexuality in Africa would have to form part of a wider process of cultural rethinking and negotiation of sexual identity. Support rather than bilateral threats should be allied to on-going grassroots campaigns which seek to mobilise public sentiment through social and educational movements that aim to generate healthy and positive attitudes and understanding towards the subject. Just as it has been done in the past, through the work between indigenous populations in Africa and international organisations on subjects such as gender equality and HIV, the same can be done for homosexuality. In the meanwhile Western governments must refrain from pseudo-moral expressions of hegemony that transform the Afro-homosexual debate into a bilateral sovereign warfare. Africans must decide for themselves when, where and how they would like to approach this issue.