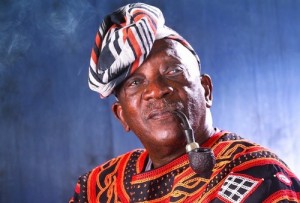

Born in 1923 in Casamance, southern Senegal, where his “crazy” fisherman father had migrated from Dakar around 1900, Ousmane Sembene has, from a marginalized and a very modest beginning, inscribed his name in world history. Expelled from school in 1936 for indiscipline, his formal education would never go beyond middle school. Also unable to take on his father’s trade because he was always seasick, in 1938 he was sent to his father’s relatives in Dakar, headquarters of the territories of French West Africa. From 1938 to 1944 he worked as an apprentice mechanic and a bricklayer. Although he was denied an opportunity of a formal education, Sembene developed a love of reading – mostly comics – and discovered cinema in the segregated movie houses of Dakar.

He spent his days at work as a manual labourer and his after work hours either reading, watching movies or, along with his neighbourhood mates, attending evenings of story telling, wrestling, and other “traditional” Senegalese cultural events . As a French citizen, in 1944, like many young Africans of his generation, he was called to active duty to liberate France from German occupation and subsequently was dispatched to the colony of Niger as a chauffeur in the 6th colonial infantry unit. Upon being discharged in 1946 at the end of the war, he went back to Dakar in the midst of charged social and political activism. That same year, for the first time, he took membership in the construction worker’s trade union and witnessed the first general workers’ strike that paralyzed the colonial economy for a month and ushered in the nationalist struggle in French Africa.

In 1947, unemployed in the thick of a war-ravaged colonial economy, Sembene left Dakar in search of a better living and also for the opportunity to feed his unquenchable thirst for learning- “apprendre à l’école de la vie.”(to learn in the school of life), as he put it many times. He migrated to France and lived in the Mediterranean city of Marseilles until 1960, the year Senegal was granted its political independence. As an black African docker who “knows” how to read and write, in Cold War Marseilles, he was soon identified by labor union leader Victor Gagnère (“papa Gagnere”, as Sembene affectionately referred to him) and enrolled in the CGT ( Confederation generale des travailleurs ), the largest and most powerful left wing workers’ union in post-war France. After back-breaking work unloading ships during the day (containers did not exist then), at night and on weekends Sembene enthusiastically attended seminars and workshops on Marxism, joined the French Communist Party in 1950, and the MOURAP (Movement against racism, anti Semitism and peace) in 1951, a political organization born of the resistence movement during WWII.

The same year, while unloading a ship, Ousmane Sembene broke his backbone. After a long recovery and now unable to sustain the physical effort required by the work of a docker, with the support of his comrades, he was assigned a post as (aiguilleur), a switchman. A new opportunity was opened to Sembene to rise from a laborer who could read and hardly write, into a well-rounded intellectual, an exceptionally cultured humanist. As his comrade and friend Bernard Worms put it: “He rose to the status of the intellectual aristocracy of the labor movement; he become “un honnête homme.” He spent most of his free time roaming public libraries, museums, theater halls, and tirelessly attending seminars on Marxism and Communism. He read everything: literature on Marxist ideology, political economy, political science, works of fiction, and history. During those Marseilles years with the passion and obsession of a convert to a new religion, Sembene also participated in the protest movements organized by the French Communist Party against the colonial war in Indochina (1953) and the Korean war(1950-1953). He also openly supported (and later wrote about) the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in its struggle for independence from France (1954-1962), and he vehemently protested against the Rosenberg trial and execution in the United States in 1953. Dreaming of the universal freedom and brotherhood mirrored by communist ideology, Ousmane Sembene also worked to educate and liberate the community of mostly illiterate and “apolitical” African workers shipwrecked at the margins of French society.

It was also in the midst of such an intense political activism that Sembene discovered other communist artists and writers: Richard Wright, John Roderigo (Dos Pasos), Ricardo Neftali Reyes (aka Pablo Néruda), Ernest Hemingway, Nazim Hikmet (Turkey), the works of French Communist writer and resistance organizer Paul Eluart, and, Jean Bruller (Vercors) co-founder of Les Editions de minuit (devoted to the publication of works dealing with resistance), and author of the classic work about the German Occupation and the Resistance, Le silence de la mer (1942) (Silence of the Sea). He also came into contact with the works of the Jamaican Communist writer Claude McKay (whose 1929 novel Banjo would influence his first novel) and the novels of Jacques Roumain, another Communist writer from Haiti and author of the classic Masters of the Dew (1947). Master’s of the Dew ‘s communist vision provided most of the powerful images in Sembene’s O pays, mon beau peuple (1957). In Marseilles he also became involved with the international Communist youth organization Les Auberges de jeunesses (Youth Hostels) and discovered the Communist theater, Le Theâtre Rouge.

However, as Sembene struggled with millions of others for revolutionary change at the international level, he also felt alienated by the quasi absence of “revolutionary” artists and writers from Africa, the voices of the masses of workers, women, and all those exploited and silenced by the combined external forces of colonialism and the internal yoke of African “tradition”. Through activism, Sembene proved that he was deeply aware of the urgent need for political and social change in Africa, but unlike many of his generation ( Sékou Touré in Guinée, Patrice Lumumba in Belgian Congo, Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, and Amilcar Cabral in Bissau Guinea who chose the political arena) he, like Palestinian writer Edward Said, strongly believed and still believes that the struggle against colonialism is not solely a fight over who should own the land but it also a contest over who should have the right to represent whom.

Thus, since 1956, while still a dock worker, and upon his return to an independent Senegal in 1960 until today, Sembene’s daily life has been devoted to the production and dissemination of emancipating and restorative images for those Frantz Fanon named the “the Wretched of the Earth”, those Africans disenfranchised and marginalized in their own society, but also whose unsung struggles are a Daily Heroism (The title of Sembene’s latest trilogy of films.) Yet for Sembene, in both literature and film, the work of “art” should not be a mere re-presentation of “reality” “une pancarte” (a political banner), as Sembene terms it. It is a work of art, a symbolic form of representation. In order to capture the imagination of the people they “speak” to and for , those symbols first must be intelligible to them. They must stem from and reflect their cultural universe. What is at work in Sembene’s literary and film creation is an endeavor to capture and project a genuine African film language and aesthetics, that would also entertain a “dialogical” relationship with other world cultures.

Ousmane Sembene started his artistic career as a poet, a short story writer, an essayist and a novelist. His first published work was Liberté (1956), a long poem in which after an extended panegyric on the a vast inventory of human accomplishment in the area of art, the poet also launched into a heartbreaking lament over his estrangement from universal beauty. The long poem closes on a dream of a free Africa whose children will redirect rivers and build monuments to its beauty. This “programmatic” poem published in Cahiers du sud, a Marseilles-based left-wing review then directed by André Gaillard, also contains the contour of Sembene’s future work.. His novels and short stories since 1956 are: Le docker noir (1956) (The Black Docker), his loosely reconstructed experiences as an black African dockworker in Marseilles; O pays, mon beau peuple (1957) is almost, thematically, a sequel to the 1956 novel.

Les bouts de bois de dieu (1960) (God’s Bits of Wood) is a masterpiece of fictionalized history, conceived from Marxist ideology and yet Sembene’s first genuinely “African” story. It was a move away from the canons of the European bourgeois novel of the nineteenth century. This third novel, a fictional recreation of the second and most comprehensive French West African railroad workers strike against their colonial bosses in 1947 was followed in 1962 by Voltaïque (Tribal Scares), a collection of short stories.

In 1963, he released L’harmattan ( a political epic of the later years of the 50’s, in the final struggle against colonial occupation). Le mandat suivi de blanche genèse (1966) (The Money Order with White Genesis), was, to be sure, a first presentation of the post-colonial situation in Senegal. Afterwards came Xala (1973), a sarcastic satire of the new and “impotent” Senegalese bourgeoisie, and Le dernier de l’empire (1981) (The Last of the Empire) which laid bare the internal contradictions and subsequent demise of an impotent and narcissistic political leadership. In 1992, a collection of two stories Niiwam et Taaw explored the despair of the Senegalese peasantry and urban youth. Guelwaar (1996), Sembene’s latest novel, an adaption of a 1993 feature film (reversing the relationship between literature and film), warned against the dangers of religious fundamentalism while showing the ironies and humiliations if a nation relies on international aid for its own economic survival .

There has been a long love affair (literally, and figuratively) between Sembene and literature. He once fell in love and married a literary scholar who specialized in his work. Sembene’s rich literary imagination fed on a vast knowledge of world literature and its masterpieces.

He died in 2007