The edifice that allows abductions to happen, from its colonial set-up to the complicity of Western actors, should be addressed and dismantled.

By Patrick Gathara – Abductions and enforced disappearances of dissidents by the Kenyan state are nothing new but have in recent months become a political lightning rod for the administration of William Ruto, focusing public attention on a highly emotive and consequential issue while keeping many blind to the history that produced it and the systems that perpetuate it.

The Gen Z movement whose protests have rocked the country since June last year has threatened to upend the way a tiny wealthy elite has managed the country’s politics and dissent for 60 years.

While the Ruto regime initially scrambled to find an effective response, alternating between acceding to demands, trying to co-opt members of the movement, and employing brutal police crackdowns on the demonstrators, it has now resorted to a time-tested tactic brought to our shores by British colonials.

The history of enforced disappearances within Kenya can be traced to the tactics employed by the British to intimidate and subjugate the natives.

“As settlers expropriated lands for the assemblage of a ‘white man’s country’, the colonial administration met challenges to colonial rule, subversion, and perceived ‘lawlessness’ with deportation, exile, and collective punishment,” write Annie Pfingst and Wangui Kimari.

These practices were developed into military theories used to suppress the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s, and were then adopted by all subsequent post-colonial regimes to quell secessionist uprisings, such as the so-called Shifta War of 1963-1967 and the Pwani Si Kenya movement. Framed as efforts to combat “terrorism”, they were also employed in a vain attempt to crush rising internal dissent and demands for democratic reform and accountability.

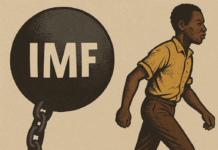

A Western-backed system

The ability of the Kenyan state to maintain this level of violence against its populace has always been contingent on the acquiescence and support of the Western world, which in the years between independence and the US-USSR détente that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, propped up Kenya as a bulwark against communism and valorised “stability” over justice.

Through the 1990s, though loudly supporting civil society groups agitating for good governance and an end to the dictatorship of Daniel arap Moi, the West still saw the need to preserve Kenya as an island of stability and “peace” in a neighbourhood characterised by economic and political collapse and chronic humanitarian crises.

In the following two decades, relations were dominated by the exigencies of the Global War on Terrorism, whose start can be dated to the attacks on the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998 that killed hundreds of Kenyans and Tanzanians.

As Kenya became a central staging ground for kidnappings and renditions, the government employed the rhetoric and tactics of GWOT to also target its domestic enemies, especially those resisting oppression in predominantly Muslim areas. This was further exacerbated following the ill-advised decision to invade Somaliain October 2011.

In 2013, with the controversial election of two politicians indicted by the International Criminal Court, Uhuru Kenyatta and Ruto, to the Presidency and Deputy Presidency respectively, it seemed the West was finally determined to break with the Kenyan elite, with many Western governments vowing to only maintain limited contacts.

But this did not last. Western resolve quickly collapsed once Kenya started drawing closer to China and Russia and away from “declining imperial powers”. All was forgiven after the ICC was forced to drop charges of crimes against humanity against the duo after witnesses kept disappearing, turning up dead, or recanting their testimony.

The waves of abductions of citizens continued and, after falling out with Kenyatta, one of Ruto’s campaign promises in 2022 was to implement the constitutional vision of an operationally independent police service and end the use of the criminal justice system as a tool for political retribution.

Taking down the edifice

In truth, very little of that has happened since Ruto took office. Despite the police being granted control of their budget, they remain free only in name and still act as lackeys of his executive. Now, as the West sacrifices its always tenuous pretensions to global moral leadership on the altar of defending Israel’s genocide in Gaza, Ruto may be calculating that he will have a free hand to do as he likes.

If, as seems likely, Europe fudges its responsibilities regarding the ICC, that will have repercussions for other spaces, including Kenya, where, as a consequence of Uhuru and Ruto’s close encounter, the threat of indictment has served as a real brake on the worst instincts of our politicians. Furthermore, openly accepting Western backing as they have done in the past could be seen as a poisoned chalice for civil society organisations.

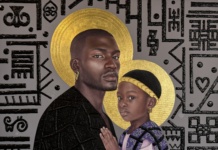

These are sadly the circumstances into which the Gen Z uprising has been born.

To understand the challenges, the abductions should be viewed through the prism of this history and placed in the contemporary context. It is not sufficient to simply say that they must end. The edifice that allows them to happen, from the colonial set-up and roots of the police to the complicity of external actors should be addressed and dismantled. For this to be achieved, all Kenyans will be required to play their part. It is no longer just a fight to be left to the youth.

And we must remember that there is no opt-out clause. When not even the country’s attorney-general can protect his son and has to plead with the president to get him released, it means no one is safe.

In the end, this is about realising the vision of the constitution of a society where the rights of all do not depend on the whims of a despot or the benevolence of the West. And that constitution will protect no one until it protects everyone.