Black farmers in Zimbabwe are saying they cannot afford to pay the compensation to their evicted White counterparts necessary to win back international funding.

In an attempt to woo back international donors and lenders, Zimbabwe’s finance minister Patrick Chinamasa announced a package of major reforms on March 9, including an annual levy on up to 300,000 Black families that have been resettled on land seized from White farmers since Robert Mugabe introduced controversial land reform policies in 2000.

Money collected from the planned levy will create a compensation fund for the White evictees in the hope of appeasing the international community.

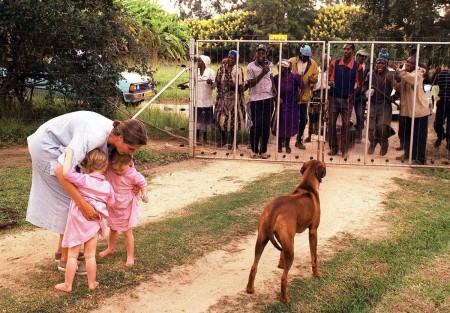

Under the plan, White Zimbabweans, who accounted for the majority of those evicted, will be compensated only for the improvements they made to the farms, while the foreign owners forced out will be paid full compensation for land and improvements.

Since 2000, when Mugabe embarked on a policy of evicting White farmers, professedly to atone for the injustice of colonialism, the inexperienced and commercially naïve Black farmers that took over have struggled to achieve pre-reform levels of commercial agricultural output.

Yields for the staple maize, for example, have fallen to an average 0.5 tonnes percent per hectare from 8 tonnes in 2000 when White farmers worked the land.

To add to their woes, the Black farmers are currently being hampered by Zimbabwe’s worst drought in a quarter of a century and are being forced to toil under a stagnating economy that has seen banks reluctant to lend and cheaper food imports from the likes of South Africa undermine their businesses.

Victor Matemadanda, secretary general of a group representing war veterans who led the land seizure drive in 2000 and are now farmers, says few will be able to pay the new levy. He told Reuters that many farmers could not even meet water and electricity bills and that it was the government’s obligation – not theirs – to pay the compensation.

Zimbabwe Commercial Farmers Union president, Abdul Nyathi, also said his members would not be able to pay compensation. “Most of the farmers face viability issues, the government will have to look at other ways of raising money,” he added.

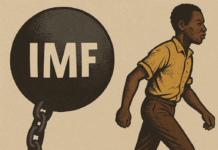

The International Monetary Fund’s head of mission to Zimbabwe, Domenico Fanizza, said this month that re-engaging the international community and improving fiscal discipline should be priorities for Harare. He said this would “reduce the perceived country risk premium and unlock affordable financing for the government and private sector”.

All agricultural land in Zimbabwe is owned by the government and, at present, farmers have no legal claim on their farms – which they say has made banks reluctant to extend loans to buy fertilisers, seed and chemicals so they can raise output. The government says it will imminently grant 99-year leases to address the issue.

“We are saying that the land should produce, but we also know what the constraints are to increase production,” says Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe governor John Mangudya, who adds: “That is why we need to finalise on the 99-year land lease agreements to make them bankable so that farmers have security of tenure. With that there is no reason why farmers should not be able to pay.”

Mugabe’s land reform program is a highly emotive issue, which has divided public opinion. Supporters say it has empowered blacks while opponents see it as a partisan process that left Zimbabwe struggling to feed itself.

“The land revolution was a necessity and if the economy was running very well farmers would be able to pay the rent,” said Matemadanda of the war veterans’ group. “The prevailing economic conditions do not allow.”