The number of Eritrean refugees arriving in the UK doubled last year to become the highest total from any single country. But could new Home Office guidance mean many others are refused asylum?

“There’s no freedom of speech [in Eritrea]. You’re not allowed to ask anything or move freely, you need to show ID to move cities,” says Mohammed. He left his home country in east Africa because he said he felt more like an “animal” than a human being.

He was one of 3,239 Eritrean migrants who made the perilous journey to the UK in 2014 to apply for asylum, according to figures seen by the Victoria Derbyshire programme. In 2013, there were 1,377.

The 28-year-old left without telling his young children where he was going, in order to protect them. “If anyone knew I was planning to escape then there will be trouble for me and my family,” he explains.

In its latest report, US-based charity Human Rights Watch says: “Torture, arbitrary detention, and severe restrictions on freedom of expression… remain routine in Eritrea.”

‘Improve my education’

Mohammed’s journey began in the country’s capital, Asmara. He crossed the border to Sudan before a long, overland trip through Israel and Turkey to Greece, guided by people smugglers.

This eastern route is now more popular with smugglers after a lull in the last two years. The number arriving in Greece rose sharply in 2014 and is likely to rise again this summer.

When Mohammed left Eritrea, he says his ambition was simply to flee to safety. He only decided the UK would become his end destination on seeing the struggles faced by refugees in Italy and France as he continued across mainland Europe. He also believed his desire “to improve my language and my life in terms of education” would be easier to fulfil in the UK.

The final leg of his journey was made via the French port of Calais, where thousands of migrants stay in makeshift camps in the hope of making it across the border.

Migrants in Calais

Calais is home to thousands of migrants hoping to make it to the UK. It took 30 attempts before Mohammed successfully smuggled himself into the UK, stowed away on board a truck.

“I was very happy at that moment. I was always trying lorries and most of them were [stopped] by the police. But this time, I don’t know how it works, but I got through.”

On arrival, he was initially held in detention, before being granted a five-year visa. He now lives in Bristol, where he says he has been accepted by locals. But new rules mean others making the same journey could be forced to return home.

Last year, 87% of Eritreans who applied for asylum in the UK were given the right to stay.

But new Home Office guidance released in March suggests only those who have been politically active in their opposition to the Eritrean government are likely to be at risk of harm for leaving Eritrea illegally if they go back to the country.

It says many other migrants will be able to return without facing retribution, “if they sign an “apology” letter [to the Eritrean government] and start to retroactively pay the 2% income tax levied on all Eritrean citizens living abroad”.

Elsa Chyrum, director of the UK-based organisation Human Rights Concern Eritrea, says she has heard from “dozens” of Eritrean refugees who have already had their requests for asylum turned down following the rule changes.

Eritrean conscripts

Men and unmarried women are conscripted for national service for indefinite periods, often into their 40s. In a recent BBC investigation, the broadcaster saw one rejection letter from March 2015 which said the applicant – who was concerned by the possibility of government retribution for having deserted on national service – had “not established a well-founded fear of persecution”.

‘Fear of prison’

For one migrant currently awaiting his immigration review – who cannot be named – it could mean he has to return home. He arrived in the UK in January having crossed the Mediterranean Sea aboard a migrant boat, before travelling through Calais.

“This was something that we were not expecting from the UK government. We left [Eritrea] to save our lives.

“If we go back, you will [spend] the rest of your life in prison… or they will kill you,” he says.

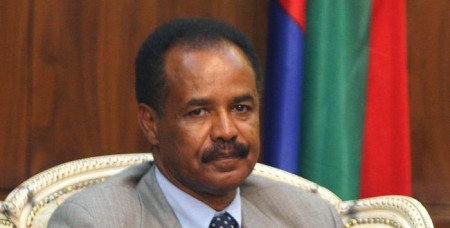

In a BBC interview earlier this year, Yemane Ghebreab, a political adviser to the Eritrean President, said that “all countries in the world” have human rights issues, but Eritrea has a “fairly good record”.

However, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a press advocacy group in New York, only North Korea rivals Eritrea as the world’s most censored nation. In addition to having the lowest cellphone ownership in the world, less than 1 percent of Eritreans can go online. The nation’s journalists are so terrified of offending the president that even reporters for the state-run news media live in perpetual fear of arrest.